SCIENCE DIPLOMACY

Casper Andersen

The Science diplomacy of ECHOES seeks to bring to the forefront decolonial perspectives on Europe's colonial heritage and use this to promote intercultural dialogue in collaboration with partners inside and outside Europe. To engage with colonial legacies and heritage, the concept of science diplomacy needs to be developed from a traditional "diffusionist" understanding towards a dialogical notion that emphasizes knowledge exchanges and acknowledges inequalities in global knowledge production.

A now well-established nomenclature divides science diplomacy into three distinct areas:

A) Diplomacy for science - in which states use diplomatic resources to promote scientific research.

B) Science for diplomacy - in which scientific cooperation is used to enhance relations between countries or groups of countries.

C) Science in diplomacy - in which scientific advice is used to inform the foreign policy of states [Royal Society 2010; Ruffini 2017].

Science diplomacy remains dominated by research in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) and medicine. However, in recent years “heritage” has explicitly entered into science diplomacy debates and initiatives [see eg. InsSciDE 2019]. There are heritage issues in all the three distinct areas of science diplomacy. For ECHOES science in diplomacy is of particular relevance.

Diffusion and its conceptual legacies in science diplomacy

Traditionally in a global perspective, science diplomacy has been conceptualized from a "diffusionist" understanding in which science is diffused from what is regarded as the scientifically advanced global north to the global south. However, as has been pointed out particularly by post- and decolonial critics it is important to acknowledge and confront the profound colonial legacies that are built into such diffusionist understandings of how and why knowledge travels and indeed into what counts as scientific and authorized knowledge in the first place. In a word, the concept of science diplomacy needs to be decolonized in order to effectively address colonial heritage contestations.

Arguably, the scholarly debate over the meaning of international science diplomacy was instigated in 1945 with the founding of UNESCO, the UN special agency whose institutional mandate included the promotion of science as a lever for international understanding and peace building among the nations of the world [Sluga 2013; Maurel 2010]. The first director of UNESCO's science sector, the British biochemist and historian of science in China, Joseph Needham, adopted what he termed "the periphery principle" as the structuring principle of Post-WWII international science diplomacy. According to Needham's periphery principle, science diplomacy should focus on supporting science and technology in the periphery of what he labelled the "bright zone" constituted by Western Europe and North America:

"For historical reasons, since modern science grew in the civilization of Western Europe, there is a "bright zone", where all the sciences are relatively advanced and industrialization highly developed. It is particularly the scientists and technologists in the far larger regions of the world outside the "bright zone" who need the helping hand of international science" [Needham 1945, 559].

Much has changed since Needham's day when formal empires were still intact in parts of the world but the periphery-bright zone imagery has proved remarkably enduring in international science. This is perhaps unsurprising given the fact that resources and infrastructures for research have remained highly unequal in global terms [UNESCO 2018].

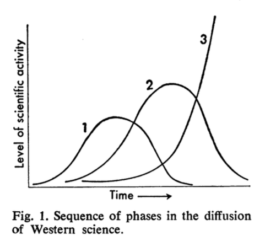

Needham's concepts were rooted in his Marxist philosophy of history but diffusionist ideas also fitted hand in glove with modernization theory "American style" that increasingly came to dominate science diplomacy discourses from the 1960s onwards. The locus classicus conceptual framing is George Basalla's 1968-article The Spread of Western Science [Basalla 1968]. Basalla presented a model to explain how what he termed "Western science" had spread from its place of origin, in 16th century Western Europe, to different parts of the rest of the world in distinct phases. In the first "expansion phase", science was carried out by expatriate Europeans in places that according to the model were essentially "unscientific" before the arrival of the European travelers and colonialists. As the European tradition replaced or marginalized non-western modes of thought a certain measure of science could begin to take root in these parts of the world as well. According to Basalla, in this phase the colonialists and their descendants, remained dependent on the resources and educational facilities of the mother countries. However, with the proper policies (and the impetus of nation building) truly scientific culture and independent research could emerge and thrive in a third phase – even to the extent that it surpassed the scientific productivity of the old scientific countries in Europe. Basalla's example of a country that had successfully gone through the three phases in the spread of Western science was, of course, the United States. The lesson was equally clear: the US model was what the newly independent countries in the "third world" should look towards to catch up – in this case not with the stumbling post-war imperial powers in old Europe but with the scientific superpower further to the West.

Figure 1: Basalla’s model depicting the three phases of diffusion. Source: Basalla, G. (1967), The Spread of Western Science, Science, 156 : 3775, 611-22.

There are fundamental problems with the diffusionist models put forward by Needham and Basalla and with their more recent versions [McLeod 2000]. These problems need to be acknowledged as we move towards approaches to science diplomacy that are more in tune with decolonial thought and practice. As a conceptual model, diffusionism depicts the world outside the global north as passive recipient of knowledge and thus relegates the former colonial world to a never-ending game of catching up with the north. Moreover, diffusionism is based exactly on the a priori hierarchical understanding of knowledge production that post- and decolonial thought is concerned with destabilizing. In the diffusionist mode of science diplomacy Europe is by definition on "transmission mode" – never on "receive mode". However, an important insight from ECHOES and from post and de-colonial thought more broadly is that Europe needs also to be on "receive mode" in order to understand the nature of contemporary contestations concerning colonial heritage. This may seem obvious but it does in fact run counter to entrenched geographical imaginations that have underpinned science diplomacy with the flow of information going (almost) exclusively from Europe and out.

Toward the dialogical understanding of science diplomacy

At the heart of science diplomacy in the context of (de)colonial heritage, thus lie concerns about the direction and flow of knowledge as well as attitudes towards receiving knowledge and listening – the key virtue highlighted in Wole Soyinka's notion of the hermeneutics of listening in his influential Burden of Memory and the Muse of Forgiveness [Soyinka 1998]. There is in this respect an important conceptual connection to the semantic field of interculturality. Here the emphasis is on interactions that enable the difficult move from a "cosmopolitan emotion of sharing the world with those who do not share our knowledge or experience" in de Sousa Santos succinct words [de Sousa Santos, 2016, 360] and towards specific practices of communication and mutual acknowledgement.

An important source of inspiration that has begun recently to influence science diplomacy discourse and practice stems from the growing attention to the role of indigenous communities and "local" forms of knowledge within the science and diplomacy nexus. Local knowledge in this context refers to knowledge and knowledge practices which "grows from interaction with local communities and movements, experience of conditions in the local environment, and the know-how involved in dealing with them" [Collyer, Connell, Maia and Morell 2019, 164]. Knowledge of this kind often draws on local history, customs and geography to engage global issues and modify "Northern" theory [Connell 2007]. This serves also as a reminder that science in the north is based on site-specific and localized practices of knowledge production and knowledge valorization [Livingstone, 2003]. The point here is not that European knowledge per definition is untrue or distorted but rather that its hegemonic position means that we may lose sight of its localized nature whereby it misleadingly can become a form of masked universalism. The environmental sciences are often at the forefront in this context because in these fields the importance of memory and history has been more firmly recognized as fundamental to successful research projects and science diplomacy [CILAC 2018].

"In a word, the concept of science diplomacy needs to be decolonized in order to effectively address colonial heritage contestations."

The focus and promotion of "local knowledge" may involve a desire for epistemological alternatives as emphasized in the decolonial literature. At other times, the agenda is not about establishing clear-cut alternative epistemes but rather about finding space for more diverse forms of knowledge within existing scientific paradigms and institutional structures. However, a dialogical ideal would emphasize a plurality of knowledge producing contexts rather than going for the conceptually easy way out by reversing hierarchies and thus run the risk of essentializing southern positionalities and epistemes.

There are at least two conceptual lessons for science diplomacy to draw from this discussion. Firstly, that science is not a neutral term in this context but it is placed at the center of contested debates. The close connection between European colonial expansion and modern science is central to the vantage point of many knowledge workers in the former colonized world [Tuhiwai Smith 2012; Roy 2018]. This historical connection, with its lasting and complex legacies, is all but ignored in the science diplomacy literature. This omission can be a hinderance to effectual science diplomacy. Secondly, this ongoing debate takes place within an unequal global knowledge infrastructure in which knowledge producers in the periphery depend on and are orientated towards the concepts, institutions, publications, and techniques of the center – processes that have been labelled "extraversion" [Hountondji, 1995]. It is because of the contested imperial legacies in science and research - and the connected processes of extroversion in contemporary knowledge production - that science diplomacy requires attentive listening as well as an openness towards plural knowledge ecologies [Diagne and Amselle 2018]. Not least in the global north center which includes the EU.

Andersen, Casper (2018), 'Science diplomacy' [online] ECHOES: European Colonial Heritage Modalities in Entangled Cities. Available at: https://keywordsechoes.com/ [Accessed XX.XX.XXXX].

Basalla, G. (1967), ‘The Spread of Western Science’, Science, 156: 3775, 611-22.

CILAC (2018), Towards science diplomacy. The role of indigenous communities and traditional knowledge, at: http://www.insscide.eu/news-media/articles/article/towards-science-diplomacy-the-role-of-indigenous-communities-and-traditional.

Collyer, F., Connell, R., Maia J. and Morell. R. (2019), Knowledge and global power. Making New sciences in the south, Clayton: Monash University Press.

Connell, R. (2007). Southern Theory. Social science and the global dynamics of knowledge. London: Polity.

de Sousa Santos, B. (2016), Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. Oxford: Routledge.

Diagne, S.B. and Amselle, J-L. (2018) En quête d’Afrique(s): Universalisme et pensée decoloniale. Paris: Albin Michel.

Hountondji, P. (1995). ‘Producing Knowledge in Africa Today The Second Bashorun M. K. O. Abiola Distinguished Lecture’. African Studies Review, 38(3), 1-10.

InsSciDE (2019), ‘Heritage’ at http://www.insscide.eu/themes/heritage/

Livingstone, D.N. (2003). Putting science in its place. Geographies of scientific knowledge. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Maurel, C. (2010). Histoire de L’Unesco. Les trente premiéres annnées 1945-74. Paris: L’Harmattan.

McLeod, R. (ed) (2000), Science and Empire. Nature and the colonial enterprise, Osiris no 15, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Needham, J. (1945) ‘The place of science and international science cooperation in the postwar world organization’, Nature,3987, 558-61.

Roy, A. (2018), Decolonize science. Time to end another imperial era, The Conversation, at https://theconversation.com/decolonise-science-time-to-end-another-imperial-era-89189.

Royal Society (2010). New frontiers in science diplomacy, at https://royalsociety.org/~/media/Royal_Society_Content/policy/publications/2010/4294969468.pdf

Ruffini, P. B. (2017) What Is Science Diplomacy? In Ruffini, P.B. (ed.) Science and Diplomacy: A New Dimension of International Relations. Cham: Springer, 11-26.

Sluga, G. (2013) Internationalism in the Age of Nationalism, University of Pennsylvania Press

Soyinka, W. (1998), The Burden of Memory and the Muse of Forgiveness, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012) Decolonial Methodologies. Research and Indigenous Peoples. London and New York: Otago University Press.

UNESCO (2018), World Science Report. Towards 2030, Paris: Unesco, at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000235406.

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under agreed No 770248

SCIENCE DIPLOMACY

Casper Andersen

The Science diplomacy of ECHOES seeks to bring to the forefront decolonial perspectives on Europe's colonial heritage and use this to promote intercultural dialogue in collaboration with partners inside and outside Europe. To engage with colonial legacies and heritage, the concept of science diplomacy needs to be developed from a traditional "diffusionist" understanding towards a dialogical notion that emphasizes knowledge exchanges and acknowledges inequalities in global knowledge production.

A now well-established nomenclature divides science diplomacy into three distinct areas:

A) Diplomacy for science - in which states use diplomatic resources to promote scientific research.

B) Science for diplomacy - in which scientific cooperation is used to enhance relations between countries or groups of countries.

C) Science in diplomacy - in which scientific advice is used to inform the foreign policy of states [Royal Society 2010; Ruffini 2017].

Science diplomacy remains dominated by research in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) and medicine. However, in recent years “heritage” has explicitly entered into science diplomacy debates and initiatives [see eg. InsSciDE 2019]. There are heritage issues in all the three distinct areas of science diplomacy. For ECHOES science in diplomacy is of particular relevance.

"In a word, the concept of science diplomacy needs to be decolonized in order to effectively address colonial heritage contestations."

Traditionally in a global perspective, science diplomacy has been conceptualized from a "diffusionist" understanding in which science is diffused from what is regarded as the scientifically advanced global north to the global south. However, as has been pointed out particularly by post- and decolonial critics it is important to acknowledge and confront the profound colonial legacies that are built into such diffusionist understandings of how and why knowledge travels and indeed into what counts as scientific and authorized knowledge in the first place. In a word, the concept of science diplomacy needs to be decolonized in order to effectively address colonial heritage contestations.

Arguably, the scholarly debate over the meaning of international science diplomacy was instigated in 1945 with the founding of UNESCO, the UN special agency whose institutional mandate included the promotion of science as a lever for international understanding and peace building among the nations of the world [Sluga 2013; Maurel 2010]. The first director of UNESCO's science sector, the British biochemist and historian of science in China, Joseph Needham, adopted what he termed "the periphery principle" as the structuring principle of Post-WWII international science diplomacy. According to Needham's periphery principle, science diplomacy should focus on supporting science and technology in the periphery of what he labelled the "bright zone" constituted by Western Europe and North America:

"For historical reasons, since modern science grew in the civilization of Western Europe, there is a "bright zone", where all the sciences are relatively advanced and industrialization highly developed. It is particularly the scientists and technologists in the far larger regions of the world outside the "bright zone" who need the helping hand of international science" [Needham 1945, 559].

Much has changed since Needham's day when formal empires were still intact in parts of the world but the periphery-bright zone imagery has proved remarkably enduring in international science. This is perhaps unsurprising given the fact that resources and infrastructures for research have remained highly unequal in global terms [UNESCO 2018].

Needham's concepts were rooted in his Marxist philosophy of history but diffusionist ideas also fitted hand in glove with modernization theory "American style" that increasingly came to dominate science diplomacy discourses from the 1960s onwards. The locus classicus conceptual framing is George Basalla's 1968-article The Spread of Western Science [Basalla 1968]. Basalla presented a model to explain how what he termed "Western science" had spread from its place of origin, in 16th century Western Europe, to different parts of the rest of the world in distinct phases. In the first "expansion phase", science was carried out by expatriate Europeans in places that according to the model were essentially "unscientific" before the arrival of the European travelers and colonialists. As the European tradition replaced or marginalized non-western modes of thought a certain measure of science could begin to take root in these parts of the world as well. According to Basalla, in this phase the colonialists and their descendants, remained dependent on the resources and educational facilities of the mother countries. However, with the proper policies (and the impetus of nation building) truly scientific culture and independent research could emerge and thrive in a third phase – even to the extent that it surpassed the scientific productivity of the old scientific countries in Europe. Basalla's example of a country that had successfully gone through the three phases in the spread of Western science was, of course, the United States. The lesson was equally clear: the US model was what the newly independent countries in the "third world" should look towards to catch up – in this case not with the stumbling post-war imperial powers in old Europe but with the scientific superpower further to the West.

There are fundamental problems with the diffusionist models put forward by Needham and Basalla and with their more recent versions [McLeod 2000]. These problems need to be acknowledged as we move towards approaches to science diplomacy that are more in tune with decolonial thought and practice. As a conceptual model, diffusionism depicts the world outside the global north as passive recipient of knowledge and thus relegates the former colonial world to a never-ending game of catching up with the north. Moreover, diffusionism is based exactly on the a priori hierarchical understanding of knowledge production that post- and decolonial thought is concerned with destabilizing. In the diffusionist mode of science diplomacy Europe is by definition on "transmission mode" – never on "receive mode". However, an important insight from ECHOES and from post and de-colonial thought more broadly is that Europe needs also to be on "receive mode" in order to understand the nature of contemporary contestations concerning colonial heritage. This may seem obvious but it does in fact run counter to entrenched geographical imaginations that have underpinned science diplomacy with the flow of information going (almost) exclusively from Europe and out.

At the heart of science diplomacy in the context of (de)colonial heritage, thus lie concerns about the direction and flow of knowledge as well as attitudes towards receiving knowledge and listening – the key virtue highlighted in Wole Soyinka's notion of the hermeneutics of listening in his influential Burden of Memory and the Muse of Forgiveness [Soyinka 1998]. There is in this respect an important conceptual connection to the semantic field of interculturality. Here the emphasis is on interactions that enable the difficult move from a "cosmopolitan emotion of sharing the world with those who do not share our knowledge or experience" in de Sousa Santos succinct words [de Sousa Santos, 2016, 360] and towards specific practices of communication and mutual acknowledgement.

An important source of inspiration that has begun recently to influence science diplomacy discourse and practice stems from the growing attention to the role of indigenous communities and "local" forms of knowledge within the science and diplomacy nexus. Local knowledge in this context refers to knowledge and knowledge practices which "grows from interaction with local communities and movements, experience of conditions in the local environment, and the know-how involved in dealing with them" [Collyer, Connell, Maia and Morell 2019, 164]. Knowledge of this kind often draws on local history, customs and geography to engage global issues and modify "Northern" theory [Connell 2007]. This serves also as a reminder that science in the north is based on site-specific and localized practices of knowledge production and knowledge valorization [Livingstone, 2003]. The point here is not that European knowledge per definition is untrue or distorted but rather that its hegemonic position means that we may lose sight of its localized nature whereby it misleadingly can become a form of masked universalism. The environmental sciences are often at the forefront in this context because in these fields the importance of memory and history has been more firmly recognized as fundamental to successful research projects and science diplomacy [CILAC 2018].

The focus and promotion of "local knowledge" may involve a desire for epistemological alternatives as emphasized in the decolonial literature. At other times, the agenda is not about establishing clear-cut alternative epistemes but rather about finding space for more diverse forms of knowledge within existing scientific paradigms and institutional structures. However, a dialogical ideal would emphasize a plurality of knowledge producing contexts rather than going for the conceptually easy way out by reversing hierarchies and thus run the risk of essentializing southern positionalities and epistemes.

There are at least two conceptual lessons for science diplomacy to draw from this discussion. Firstly, that science is not a neutral term in this context but it is placed at the center of contested debates. The close connection between European colonial expansion and modern science is central to the vantage point of many knowledge workers in the former colonized world [Tuhiwai Smith 2012; Roy 2018]. This historical connection, with its lasting and complex legacies, is all but ignored in the science diplomacy literature. This omission can be a hinderance to effectual science diplomacy. Secondly, this ongoing debate takes place within an unequal global knowledge infrastructure in which knowledge producers in the periphery depend on and are orientated towards the concepts, institutions, publications, and techniques of the center – processes that have been labelled "extraversion" [Hountondji, 1995]. It is because of the contested imperial legacies in science and research - and the connected processes of extroversion in contemporary knowledge production - that science diplomacy requires attentive listening as well as an openness towards plural knowledge ecologies [Diagne and Amselle 2018]. Not least in the global north center which includes the EU.

Andersen, Casper (2018), 'Science diplomacy' [online] ECHOES: European Colonial Heritage Modalities in Entangled Cities. Available at: https://keywordsechoes.com/ [Accessed XX.XX.XXXX].

Basalla, G. (1967), ‘The Spread of Western Science’, Science, 156: 3775, 611-22.

CILAC (2018), Towards science diplomacy. The role of indigenous communities and traditional knowledge, at: http://www.insscide.eu/news-media/articles/article/towards-science-diplomacy-the-role-of-indigenous-communities-and-traditional.

Collyer, F., Connell, R., Maia J. and Morell. R. (2019), Knowledge and global power. Making New sciences in the south, Clayton: Monash University Press.

Connell, R. (2007). Southern Theory. Social science and the global dynamics of knowledge. London: Polity.

de Sousa Santos, B. (2016), Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. Oxford: Routledge.

Diagne, S.B. and Amselle, J-L. (2018) En quête d’Afrique(s): Universalisme et pensée decoloniale. Paris: Albin Michel.

Hountondji, P. (1995). ‘Producing Knowledge in Africa Today The Second Bashorun M. K. O. Abiola Distinguished Lecture’. African Studies Review, 38(3), 1-10.

InsSciDE (2019), ‘Heritage’ at http://www.insscide.eu/themes/heritage/

Livingstone, D.N. (2003). Putting science in its place. Geographies of scientific knowledge. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Maurel, C. (2010). Histoire de L’Unesco. Les trente premiéres annnées 1945-74. Paris: L’Harmattan.

McLeod, R. (ed) (2000), Science and Empire. Nature and the colonial enterprise, Osiris no 15, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Needham, J. (1945) ‘The place of science and international science cooperation in the postwar world organization’, Nature,3987, 558-61.

Roy, A. (2018), Decolonize science. Time to end another imperial era, The Conversation, at https://theconversation.com/decolonise-science-time-to-end-another-imperial-era-89189.

Royal Society (2010). New frontiers in science diplomacy, at https://royalsociety.org/~/media/Royal_Society_Content/policy/publications/2010/4294969468.pdf

Ruffini, P. B. (2017) What Is Science Diplomacy? In Ruffini, P.B. (ed.) Science and Diplomacy: A New Dimension of International Relations. Cham: Springer, 11-26.

Sluga, G. (2013) Internationalism in the Age of Nationalism, University of Pennsylvania Press

Soyinka, W. (1998), The Burden of Memory and the Muse of Forgiveness, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012) Decolonial Methodologies. Research and Indigenous Peoples. London and New York: Otago University Press.

UNESCO (2018), World Science Report. Towards 2030, Paris: Unesco, at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000235406.

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under agreed No 770248